It always makes me cry.

Towards the last third of my play Whale Fall, there is a scene in which the character of Steven (inspired by myself) is recalling a story of taking his daughter Becca (inspired by own daughter of the same name) to Marineland. Specifically, the scene depicts Steven and Becca seeing Kiska, the so-called “loneliest orca in the world”, alone in her tank swimming in circle after endless circle.

The scene is based on reality. And that’s why it makes me cry.

In 2012, shortly after the birth of my daughter, my wife and I traveled to Marineland. I had never been there but, as Steven says in the script, the “ugly orange tiles on the rooftops of the buildings had all been lifted from the commercials that filled my childhood”. As anyone who grew up in the 80s can tell you, Marineland formed a signature part of television tourism. The images of breaching orca, playful seals and the familiar jingle “Everyone Loves Marineland” were odd touchstones. Of course, back then, I had no idea of the horrific implications of these images.

On this particular trip, I knew something was wrong. I was a new father, living in a new city, and trying to find my way around. And here I was, finally visiting this touchstone from my past. And it was turning out awful. Within an hour of our arrival, I wanted to leave. But then, my daughter and I saw Kiska. As anyone who has seen the play can recall, my daughter’s fascination with orcas started the day she saw Kiska… even if she can’t quite remember it now all these years later.

Captured off the coast of Iceland in 1979 at approximately three years old, Kiska was eventually transferred to a tank at Marineland. Kiska gave birth to five calves while in captivity. Tragically, all them died while they were young. During her captivity, Kiska often showed the kind of abnormal and repetitive behavior–banging her head against the tank, swimming in circles or floating listlessly–that whale biologists have identified as signs of boredom and extended stress.

Years later, the Kiska scene in Whale Fall was one of the first scenes I wrote when crafting the play. It was the first scene I brought to the Theatre Aquarius Junction when I started writing, the first scene I shared with other artists, and it always hits me so hard because of how firmly it’s rooted in reality,

Earlier this year, while on a trip with my family, I heard news: Kiska had died.

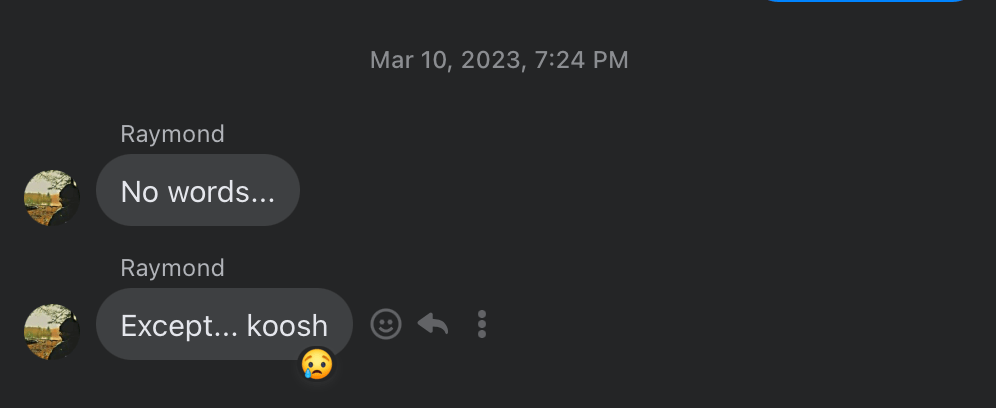

It wasn’t a surprise. Tragically, as the lone orca held in captivity at Marineland for years, it was perhaps a surprise that she had lived as long as she did. But it hurt all the same. When I sent the news to the rest of the Whale Fall team, the responses ranged from sorrow to relief that she was no longer suffering. But, perhaps, the most heartfelt was Ray:

“Koosh” is the signature line of the play. It represents the sound that orca make as they exhale and, in so many ways, has come to symbolize the enduring power of these animals in the story of the play.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Kiska since the company began revisiting the play in preparation for our run in Vancouver this September. Since premiering the show last year, the Whale Fall team have been honing the piece and revisiting almost every facet of the script and production. Certainly, there are new scenes that were added. And, of course, there are bits that have been cut. But, honestly, it’s the things we haven’t changed that are most intriguing.

And one of those things is Kiska.

The devastating authenticity of this scene remains pretty much intact from when I first wrote the words inspired by that trip many years ago.

It is my hope that when we take this show out to Vancouver, in front of audiences who may well have had the opportunity to see these magnificent animals swimming in the Georgia Straight or the Salish Sea – literally in their own backyards – that the message of Whale Fall will hits them in the same way that the Kiska scene always hits me.

Good-bye Kiska.